By Kenneth Christiane L. Basilio, Reporter

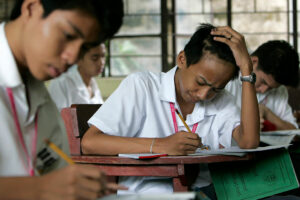

THE PHILIPPINE education system is walking on thin ice, with nine of 10 Filipinos unable to read and understand a simple age-appropriate text at age 10, according to the World Bank.

The coronavirus pandemic made that worse as the country endured the longest school closure among 122 countries, along with highly unequal access to the internet and digital learning resources.

The government should address this crisis if the Philippines wants to realize its growth potential. Failure to do so would lead to economic stagnation, according to an education expert.

Reforming the country’s education system is no small task, and the state should look at slowly improving the sector, Elvin Ivan Y. Uy, executive director of the Philippine Business for Social Progress, said in an interview.

“If we are unable to properly capacitate, educate, and develop our human capital, then the Philippines will be caught in a middle-income trap,” he said. “For education, the hope is you are improving every day, every year. You can at least say that this school year is better than the last… it shows that there is progress.”

The Philippines’ human capital indicators are “lackluster” compared with other countries, the World Bank said in a report in June. A Filipino child could only achieve half of their productive potential by the time they reach 18 years, it said.

“The Philippines is currently missing out on almost half of its human capital potential,” the multilateral lender said. “The Philippines has the lowest human capital index, which warns of the constraints to productivity of the next generation of workers given the prevailing rates of mortality, schooling achievements, and health outcomes.”

“The next five to 10 years will define whether we can maximize our demographic dividend window by 2049,” Mr. Uy said.

Filipino students were among the world’s weakest in math, reading, and science, according to the 2022 Program for International Student Assessment. The Philippines ranked 77th out of 81 countries and performed worse than the global average in all categories.

Institutional neglect is largely to blame for the failures of the system, said Justine B. Raagas, executive director of the Philippine Business for Education.

“Despite various reforms and initiatives, the country continues to grapple with issues such as low student performance in international assessments, insufficient resources, overcrowded classrooms and a lack of qualified teachers,” she said in an e-mail.

NEW CURRICULUMVice-President and former Education Secretary Sara Duterte-Carpio introduced in August 2023 the so-called Matatag (stable) curriculum, focusing on subjects that will produce “competent, job-ready, active and responsible citizens,” according to the Department of Education (DepEd).

The curriculum will be implemented in batches, starting with kindergarten, grades 1, 4, and 7 in the school year 2024-2025. It will be fully implemented by 2026-2027.

Pasig Rep. Roman T. Romulo said the curriculum, which seeks to “decongest” competencies and subjects, would improve education quality.

“Under the Matatag curriculum, we will not only limit competencies but also subjects,” Mr. Romulo, also a co-chairperson of the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EDCOM II), said in an interview in mixed English and Filipino.

“We will focus on functional literacy and numeracy, which is what we really need because if you look at it, we score low in reading comprehension and in numeracy,” he added.

Matatag claims to decongest the old curriculum by 70%, while still ensuring that the heavier weight of the learning areas would be on English, Filipino, Science, Mathematics, and Technical Livelihood Education.

Education authorities should assess the new curriculum to determine if it’s effectively addressing learning losses, Ms. Raagas said. She added that it should be “adaptable to local contexts,” allowing local school authorities to have a say in what should be included in the syllabus.

“The curriculum should be adaptable to local contexts, allowing schools and teachers flexibility, while decentralizing decision making to empower local authorities,” she said.

Ms. Raagas said the Education department is too centralized, hindering its ability to quickly enforce policy interventions.

DepEd’s authority should be cascaded to local governments, she added, noting that strengthening local education boards would make community-based learning programs possible.

The Education department is already “functionally decentralized,” Mr. Uy, a former DepEd assistant secretary, said. “When I say functional, responsibilities from what used to be at the national or regional level were already transferred to the field or school level.”

The problem lies with funding sources for regional and local school boards, he said, noting that DepEd failed to decentralize fiscally. “The funds are still controlled by the National Government,” he added.

DepEd’s proposed budget for 2025 increased by 4.2% to P745.8 billion, while the budget for education as a sector inched up by 0.9% to P977.6 billion, according to a summary from the Budget department. The latter covers the Education department, Commission on Higher Education, Technical Education and Skills Development Authority, and state universities.

Education’s share in the 2025 budget fell to 15.4% from 16.8% this year.

“It’s not just the amount, but the quality of spending [that we have to consider],” Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Arsenio M. Balisacan said in an interview. “If we can improve the quality of spending, even a small amount can do a lot.”

COLLEGE WOESThe college education system also faces issues, including incompetency among graduates and the lack of emphasis on soft skills, Ms. Raagas said.

“One significant issue is the lack of collaboration between industry and academia, resulting in graduates who are not adequately prepared for the workforce,” she said. There’s also a problem with redundant competencies — many skills taught in senior high school are repeated in college, wasting valuable time and resources.”

In a report to the House of Representatives, the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) said three of 10 Filipino college students who were supposed to graduate this year dropped out.

About 37% of students dropped out in 2021-2022. The college dropout rate spiked to 41.03% the following school year before settling at 29.4% in 2024, according to CHED data.

CHED has started enforcing key policies that could improve higher education, chairman Prospero E. de Vera III said in an interview.

He said CHED now requires state universities and colleges to submit a certificate of program compliance, which the agency could review to check if their degree complies with minimum education standards.

Mr. De Vera is also pushing internationalization efforts. “If our universities are willing to benchmark and compare themselves with the top universities in the world and adopt good practices, they will definitely improve what they are doing in teaching and research.”

Internationalization would also let graduates of Philippine schools find jobs overseas, he added.

“If the curriculum for nursing in a Philippine university is the same as the curriculum in universities abroad, then they could find employment [easily],” Mr. De Vera said.

A joint education master plan crafted by the government and business stakeholders would benefit the education sector as a whole, Ms. Raagas said.

“A combined government-business master plan could enhance curriculum relevance, ensure proper resource allocation, and foster public-private partnerships for innovative programs,” she said. “This collaboration would make sure graduates have the necessary skills and knowledge to succeed, boosting the country’s economic development.”

Mr. Uy said a long-term learning master plan would help chart the direction of the country’s educational system.

Having a joint master plan would produce students with the skills needed in the job market, Ms. Raagas said.

“Universities can be informed about the competencies their graduates need so they can change the curriculum to ensure that students are industry- or work-ready upon graduation,” Mr. De Vera said.

“The problem is that if the industry has no input in the curriculum, graduates will need retraining. So we need to adjust the curriculum to meet the needs of the industry.”

Mr. Romulo said he’s pushing for businesses to have more say in technical-vocational (tech-voc) skill training programs. “There needs to be a bigger role because the tech-voc track is about skills training,” he said.